Menopause and Naturopathic Therapies

Western medicine has not focused on the research and treatment of menopausal transition symptoms, so many women who seek help from their clinical health-care provider are left with no information, help, or hope.

Additionally, many women desire personalized care, are biased to believe that natural remedies are better than manufactured drugs, and are challenged by the cost of those drugs. [1] These factors have led to a surge in naturopathic treatment– based on a whole body treatment to manage symptoms during the menopausal transition.

Naturopathic practitioners that have received training in the field of women’s health are well equipped to listen and hear women when they present with challenging perimenopausal symptoms. Not all naturopathic practitioners have the same level of knowledge and training or specialization so do your research when seeking out medical advice.

What are Naturopathic Practitioners?

‘Naturopath’ is a commonly used term to describe different types of naturopathic practitioners. Be aware that there are significant differences in the amount of training, experience, and knowledge among different types of naturopathic practitioners. For example, naturopathic physicians, also known as naturopathic doctors (ND) or doctors of naturopathic medicine (NMD) have training at an accredited four-year graduate level program. The training they receive is similar to conventional medical training, with additional training in nutrition, psychology and alternative (also called complementary) therapies including herbal medicines. NDs and NMDs are regulated in many provinces and states, and in some, they have the ability to write prescriptions. NDs and NMDs often assess patients with the use of specialized tests, many of which are not covered by the average health plan.

Naturopaths are not formally trained in any programs nor can they be licenced or prescribe medicines. Many naturopaths are homeopaths, practitioners that use only homeopathic remedies, which are made from diluted natural substances.

Traditional healthcare providers may have training in naturopathic medicine or be fully trained in naturopathy and have a license as an ND or MND.

Finding a trusted source to provide information about non-western (ie non-hormonal) menopausal therapies can be difficult. [2] If you are considering naturopathic treatment, it is really a case of buyer beware – you need to ask about your practitioner’s training and licencing and consider if that training meets your standards for care.

North American Menopause Society (NAMS) & Non-hormonal Management?

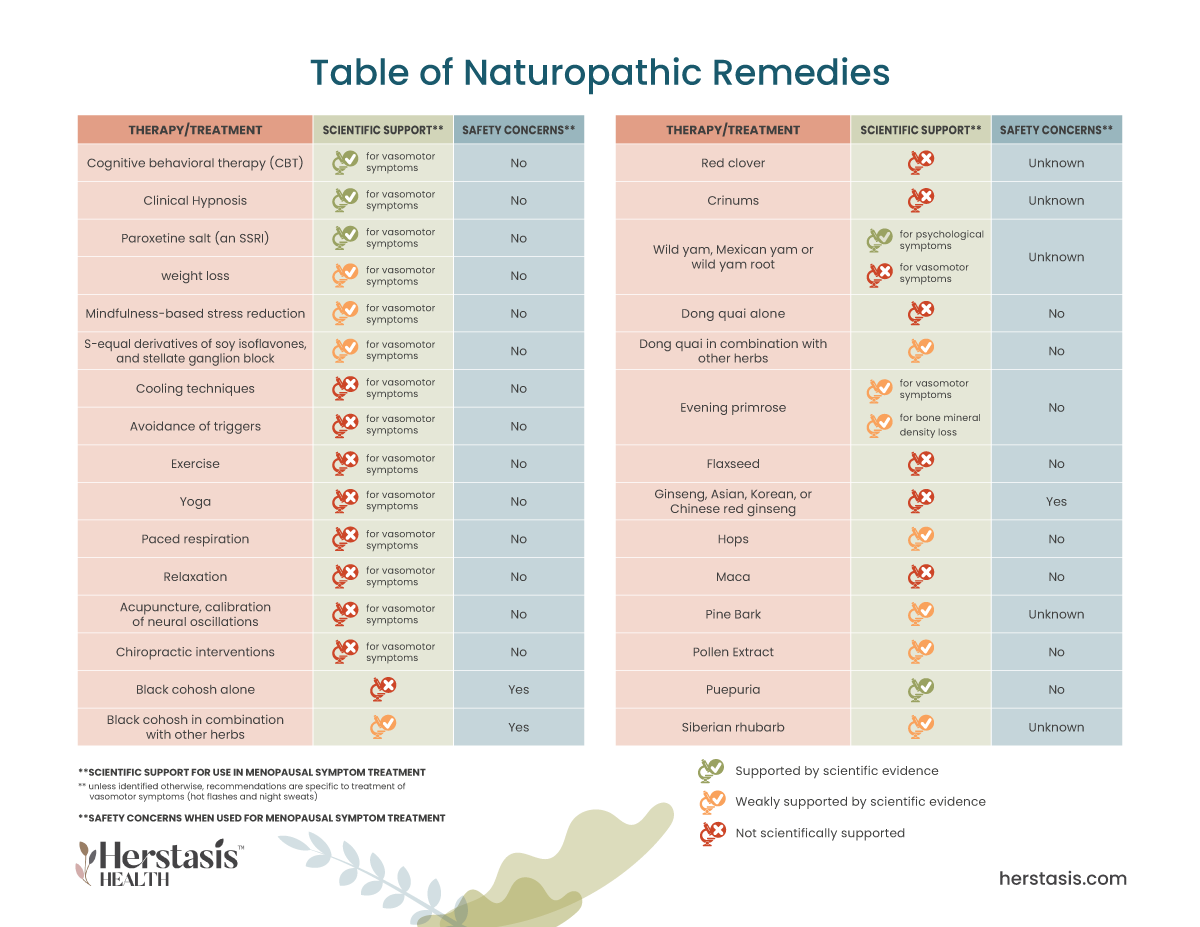

In 2015, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) released a position statement on non-hormonal management of the most common perimenopause symptoms called Vasomotor Symptoms (VMS)[4] This position statement is aimed at clinicians, to keep them informed about what the scientific evidence shows with respect to the many non-hormonal (naturopathic) management options. The goal is to provide evidence-based guidance that can prevent the use of inappropriate or ineffective therapies and to support the use of effective ones.

NAMS Recommendations

NAMS Recommended:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a common form of talk therapy, and clinical hypnosis have been shown to be effective in reducing vasomotor symptoms (VMS).

- Paroxetine salt is the only non-hormonal medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of VMS, although other selective serotonin reuptake/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), gabapentinoids, and clonidine show evidence of efficacy.

NAMS Recommended with caution:

- weight loss

- mindfulness-based stress reduction

- S-equol derivatives of soy isoflavones, and stellate ganglion block (additional studies of these therapies are warranted)

NAMS Does not recommend at this time:

There are negative, insufficient, or inconclusive data suggesting the following should not be recommended as proven (ie scientifically supported and guaranteed) therapies for managing VMS, although many may help individual women:

- cooling techniques

- avoidance of triggers such as alcohol and spicy food

- exercise

- yoga

- paced respiration

- relaxation

- over-the-counter supplements and herbal therapies

- acupuncture, calibration of neural oscillations

- chiropractic interventions

Note that these recommendations are for vasomotor symptoms only. There are no recommendations from governing or licensing bodies on the use of naturopathic treatments for menopausal symptoms other than vasomotor symptoms.[4]

Research

Research has shown that most women surveyed do not feel fully informed or have concerns about various naturopathic treatment options. One national survey of 781 women in the menopausal transition showed that 75% of those women did not feel fully informed about herbal products, 64% were concerned and uncertain about herb-drug interactions, and 61% of those women were not confident about the dosages required for herbal remedies. Another research survey showed that over half of the respondents were confused about the options to best treat their menopausal transition symptoms.[2]

Science

At Herstasis we pride ourselves on bringing the latest quality scientific information to our readers. Many naturopathic remedies have not been fully assessed with rigorous science, but just because they haven’t been studied using scientific methodology does not necessarily mean they aren’t valuable as treatments. However, Herstasis is a science-based organization, so we look to the evidence to see what the science says before supporting the use of any natural remedies.

Evidence

Evidence is scientific proof from well-conducted, good-quality scientific trials that have been carefully designed to answer specific questions. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the best way to get reliable evidence on the effectiveness of medical treatments (interventions). [3] All of the research results referenced in the Science section below are from carefully designed high-quality studies, the majority of which are RCTs.

The Science

The following list of naturopathic remedies is not exhaustive, but it does include all the naturopathic remedies that have had rigorous scientific studies performed to assess their effectiveness.

Understanding Perimenopause Naturopathic Remedies

Black cohosh is the most studied medicinal plant in North America and it is also the most commonly purchased botanical treatment for menopausal symptoms. The rhizome (root) is harvested in fall and may be used in fresh or dried form. The primary active constituent of the black cohosh root is believed to be the terpene glycoside fraction, including actein and cimifugoside.[5] The rhizome also contains other potentially biologically active substances, including alkaloids, flavonoids, and tannins.

The actual mechanism by which black cohosh relieves certain perimenopause symptoms is still under study. Several hypotheses have been proposed, including black cohosh acting as a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), acting through serotonergic pathways, acting as an antioxidant, or acting on inflammatory pathways. Results show that black cohosh can act through different biological pathways and that the mechanisms by which it acts involve inflammatory pathways rather than pathway involving estrogens. [6]

In a review of 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs, the gold standard of scientific evidence-based data collection), with 2027 participants in total focused on measuring the effects of oral A. racemosa on menopausal symptoms, including VMS, sexual dysfunction, vulvovaginal symptoms, bone health, and quality of life, researchers concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of black cohosh for menopausal symptoms at this time, but that there was sufficient evidence to warrant further investigations. In the results of the studies that were included in the review article, no significant difference was found between the use of black cohosh and a placebo in the frequency of hot flashes or in menopausal symptom severity scores. [7]

In an RCT with 301 women comparing isopropanolic black cohosh extract (black cohosh in an alcohol solvent) in combination with ethanolic St John’s wort (St John’s wort in an an ethyl alcohol solvent) to a placebo, scores on the Menopause Rating Scale decreased by 50% in the treatment group compared to 19% in the placebo group. Depression also significantly decreased compared with placebo. In a second RCT comparing the effects of black cohosh plus St John’s wort, results showed significant improvements in the treatment group compared with placebo.

However, it is difficult to conclude from these studies if black cohosh is beneficial in itself or only in combination with other herbs. The overall conclusion is that more research is needed using standardized preparations to ensure comparability across studies and to isolate the active ingredients in the positive effects. [7]

Black cohosh does have side effects for some women. These include stomach and bowel problems, rashes, headaches, dizziness, and nausea. These side effects usually go away when women stop taking them. [3][8]

There have been cases of acute hepatitis associated with the use of black cohosh, but after examining all reported cases, the US Pharmacopeial Convention’s Dietary Supplements-Botanicals

Expert Committee found only 30 reports possibly related to black cohosh. As a result, black cohosh products must carry a warning statement: “Discontinue use and consult a healthcare practitioner if you have a liver disorder or develop symptoms of liver trouble, such as abdominal pain, dark urine, or jaundice.”[2] Signs of liver toxicity include tiredness, loss of appetite, yellowing of the skin or eyes, darker urine, and upper stomach pain and nausea. Women are also advised not to take black cohosh together with estrogen. Black cohosh is also not suitable for women who have breast cancer. [3]

Chasteberry is the fruit from the chaste tree, found in Asia and in the Mediterranean region. It contains phytoestrogens, natural substances that mimic estrogen, which may explain why it has traditionally been used to help with menstrual issues. One study found that anxiety and hot flashes were reduced in symptomatic menopausal women taking chasteberry supplements for 8 weeks. [14]

Crinums are widely used in folk medicine in South Asia and are thought to have antitumor, immune-modulating, analgesic, and antimicrobial effects. One branded product, Crila, is sold specifically to manage vasomotor symptoms. No scientific studies of Crila can be found in the current medical research literature.[2]

Dong quai, also called dang gui or tang kuei, is used in traditional Chinese medicine, often with a mix of other herbs, to treat gynecological problems. While it has been thought to act as an estrogen, studies on humans have shown no evidence of this.

One RCT looked at the effects of Dong quai on vaginal cells, endometrial thickness, and menopausal symptoms among 71 women. The results showed no difference between the treatment group and a control group using a placebo for impacts on menopausal symptoms (including vasomotor symptoms), nor was there any difference in the Kupperman Index scores; levels of FSH, LH, and estradiol; vaginal maturation index; or endometrial thickness. Responses to the results include the criticism that the dose given was lower than that used in traditional Chinese medicine, and the fact that Dong quai is usually used with other herbs. [2]

A different RCT compared a combined preparation of A. sinensis and Matricaria chamomilla (german chamomile), to a placebo in 55 women reporting vasomotor symptoms. The results showed a clinically significant improvement in the frequency and intensity of hot flashes (90%-96%) compared with placebo (15%-20%) over the 3-month trial.[8]

Another RCT study looked at the effects of A. sinensis combined with other herbs (including black cohosh, milk thistle, red clover, and American ginseng) on 50 women experiencing vasomotor symptoms. At 12 weeks, the results showed that participants receiving the herbal mixture reported a 73% decrease in hot flushes and a 69% decrease in night sweats, compared with 38% and 29% improvement in the placebo group, respectively. The treatment group also reported greater improvements in sleep quality.[8]

Based on these three studies, it is possible that Dong quai is effective only when combined with other herbs.

There are several safety concerns associated with Dong quai, including interactions with other medications and herbs, photosensitization, anticoagulation, and possible carcinogenicity. [8]

Evening primrose is a flowering plant rich in linolenic acid and γ-linolenic acid (essential omega-6 fatty acids). Evening primrose oil (EPO) has been recommended for a wide array of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders including allergies, eczema, arthritis, diabetic neuropathy, mastalgia/mastodynia, and inflammatory or irritable bowel disease, in addition to women’s health conditions such as hot flashes in the menopausal transition.

In one RCT looking at hot flashes, 56 women were randomized to take either evening primrose oil at a dose of 500 mg per day or a placebo for 6 months. The results showed that evening primrose oil was ineffective, with hot flashes declining by 1.0 per day with evening primrose oil and by 2.6 per day with placebo. [2] [8]

Another RCT compared treatments of 500 mg of evening primrose oil daily to a placebo on vasomotor symptoms. Hot flash frequency was reduced by 39% (evening primrose oil ) and 32% (placebo) after 6 weeks. Hot flash severity decreased by 42% (evening primrose oil) and 32% (placebo) and hot flash duration decreased 19% (evening primrose oil) and 18% (placebo).[8] These results are statistically significant, however the improvements seen were not clinically significant – in other words, you couldn’t tell them apart in a clinical setting.

Two RCTs have been conducted to investigate the effects of evening primrose oil on bone mineral density loss pre-menopause versus post- menopause. Both pre- and postmenopause participants were randomly assigned to receive evening primrose oil (4.0 g) in combination with marine fish oil (440 mg) and calcium (1.0 g) or to receive calcium (1.0 g) alone. All participants in both studies, irrespective of treatment or menopause phase, showed significant increases (1%) in bone mineral density. Given these findings, there is not currently enough evidence to support the use of EPO for menopausal symptoms at this time.[8]

Flaxseed, or linseed, contains abundant lignans, which are polyphenolic sterols that can produce enterodiol and enterolactone, two weakly estrogenic sterols. Humans require highly milled flax flour and flax meal, not flaxseeds themselves, to access the lignans, because the lignans are contained in the flaxseed cell walls and need to be crushed to be released. Flaxseed oil is a good source of polyunsaturated fatty acids but it provides no lignans. [2]

One review study of the use of flaxseed as a menopausal remedy assessed five studies with a total of 437 participants divided into flaxseed vs placebo trials. None of these reported improvements in vasomotor symptom frequency or severity that exceeded the placebo trials. However, one of the studies in the review showed that while the mean hot flash severity score change was not statistically significant (4.9 in the flaxseed group vs 3.5 in the placebo group), there was a significant improvement noted in the degree to which vasomotor symptoms interfered with leisure activities. [2]

This combined evidence for flaxseed does not support its use for improvement of vasomotor symptoms.

One study of ginseng, using a product called Ginsana, 384 postmenopausal women were randomized to a Ginsana or a placebo group. After 16 weeks, women taking Ginsana showed slightly better, but not statistically significant, overall symptom relief, particularly depression, well-being, and other health scores, but not vasomotor symptoms. Ginseng had no effect on FSH, estradiol, endometrial thickness, vaginal maturation index, and vaginal pH. [2]

Another RCT measured the frequency of hot flashes after treatment with either Korean red ginseng or a placebo and found no statistically significant difference between groups. A follow-up study however, found that ginseng improved both Kupperman Index and Menopause Rating Scale scores but did not see any effect on hot flash scores within either scale.

It appears that ginseng is not effective for treatment of vasomotor symptoms. There have also been safety issues identified, primarily around taking ginseng in energy drinks at the same time as taking other stimulants. [2]

The female hops flower, also called the seed cones or strobiles, are used to make beer and to add flavour to other grains. Hops makes a flavonoid (8-prenylnaringenin) that is thought to have estrogenic effects, even more so than soy-derived isoflavones.[2]

The scientific evidence for the use of hops to treat menopausal transition symptoms is both limited and inconsistent. One RCT included 67 women randomized into one of two standardized doses of hops extract (100 μg or 250 μg) or a placebo. The results showed that 100 μg of hops was better than placebo at 6 weeks but not at 12 weeks. The 250-μg hops treatment was no better than a placebo. [2]

A second study had 36 women randomly assigned to hops or placebo treatment for 8 weeks, followed by another 8 weeks of the opposite treatment (the hops started the placebo treatment and the placebo started hops treatment). Outcomes were assessed against the Kupperman Index and the Menopause Rating Scale at the start (0), 8, and 16 weeks. [10]

After 8 weeks, both the hops and the placebo treatment significantly improved all outcome measures when compared to baseline with somewhat higher average reductions for placebo than for the active treatment. After 16 weeks only the active treatment after the placebo treatment further reduced all symptom measures on the Kupperman Index, whereas placebo treatment after hops treatment resulted in an increase for all outcome measures. No significant reduction was seen based on the Menopause Rating Scale after 16 weeks. [10]

Labisia pumila is an herb from Malaysia used in traditional medicine. Eurycoma longifolia is a flowering plant found in Southeast Asia, also used in traditional medicine. They can be used individually for a variety of disorders, and they are combined together into a supplement for women’s health, specifically for hot flashes. The only study looking at its specific use for menopause symptoms found no significant differences between the control group (who received a placebo) and the treatment group. [15]

Maca is a cruciferous root grown only in the central Peruvian Andes at 12,000 to 14,000 feet altitude. It is recommended as a treatment for female hormone balance and also for strength and stamina, athletic performance, anemia, and fertility and as an aphrodisiac.[2]

The mechanism of action of maca on male and female hormones is still unknown, but maca contains a weak phytosterol, β-sitosterol, also found in several other botanicals, such as saw palmetto, which is often recommended as a treatment for prostate problems. Both methanolic and aqueous extracts of maca exhibit estrogenic activity in the lab, but no studies have yet seen estrogenic effects in natural settings. [2]

In a systematic review, four studies on maca and the treatment of menopausal symptoms were evaluated. All showed improvements in Greene Climacteric Scale or Kupperman Index scores, but all were poor quality with poor trial design, very small sample sizes, or limited reporting of study data. [11]

Thus, at this time the evidence does not support the use of maca for vasomotor symptoms. More data are needed to evaluate the usefulness of maca for other menopausal transition symptoms and to determine the safety of maca use.[8]

Milk thistle is a flowering plant that is used to make an extract used in herbal medicine. It is usually used to treat liver and gallbladder problems and to promote the production of breast milk. The active ingredient in milk thistle is called silymarin, which is made up of a group of plant compounds including silibinin and flavonolignants. Milk thistle is safe and generally well tolerated with the exception of people with allergies to the Asteraceae/Compositae family of plants.

The use of milk thistle to help with menopause symptoms, particularly hot flashes and night sweats, is relatively new. Little research has been done on milk thistle extract and menopause symptoms. The one small study that has been done concluded that, after 12 weeks of milk thistle extract (at 400 mg per day), there was a significant decrease in the frequency and severity of hot flashes compared to a placebo. Note that there were only eight women in the study – four women in the treatment group and four women in the placebo trial, so more research needs to be done with larger numbers of participants to confirm these findings. [16]

Pine bark from P. pinaster is a source of proanthocyanidins that are thought to be antioxidants and that are sold under the registered trademark name Pycnogenol.[2]

Three RCTs looked at using Pycnogenol to treat menopausal symptoms. The first randomized 200 women to 200 mg or placebo. The results showed significant improvements in all domains of the Women’s Health Questionnaire [12]. In the second study, 38 women were given 100 mg Pycnogenol daily for 8 weeks. These women showed more improvement in vasomotor symptoms compared to a control group of 32 untreated women. In the third study, 170 perimenopausal women were randomly assigned to a treatment of 30 mg Pycnogenol twice daily or to a placebo. After 12 weeks, symptoms were significantly more improved with treatment than placebo, based on improved scores in the Women’s Health Questionnaire vasomotor scores and total Kupperman Index scores.[2]

These studies suggest pine bark, in the form of Pycnogenol, could be beneficial for relieving symptoms. More high quality data is needed to confirm the most effective dose. Pycnogenol is possibly safe, but the safety of other pine bark preparations cannot be assured. [2]

Multiple commercial extracts have been made from flower pollen and are marketed under the brand names Serelys, Femal, Femalen, and Relizen. The active ingredients are pollen cytoplasmic extract (GC Fem) and pistil extract (PI 82), and the mechanism of action is hypothesized to be antioxidant and anti-inflammatory.

Relizen contains 40 mg of GC Fem and 120 mg of PI 82, and some older forms also contain vitamin E. Oddly enough, the manufacturer states that there is no pollen in the product and that it is safe for persons with pollen allergies. Lab and animal research have shown that pollen extract does not specifically bind to estrogen receptors and so has no estrogenic activity.[2]

There is a single RCT looking at the impact of pollen extracts on menopausal transition symptoms. Sixty-four women recorded their symptoms using the Menopause Rating Scale and personal diaries, and were then randomized to a Femal treatment or a placebo treatment. After 12 weeks the women in the Femal treatment group reported a 22% (Menopause Rating Scale) and 27% (diary) reduction in hot flashes, while the women in the placebo treatment reported a 4% increase in hot flashes. Additionally, for the Femal treatment group, all symptom categories rated on the Menopause Rating Scale showed improvements in other quality-of-life parameters compared to placebo. [8]

However, more studies are warranted to further explore the impact of pollen extract on menopausal transition symptoms.[8]

Puerpuria is a plant found in northern and northeastern Thailand and Myanmar that is estimated to contain 8% to 10% isoflavone by dry weight.[2]

The only well designed study looked at the effects of puerpuria on menopausal symptoms. In the first, 52 hysterectomized, symptomatic women were randomized to P. mirifica at either 25 mg or 50 mg per day for 6 months. No placebo treatment was included. The baseline scores using the Greene Climacteric Scale, the baseline scores were 24.19 ± 9.11 and 23.19 ± 7.89, respectively. After 3 months of treatment, scores were 17.92 ± 10.40 for the low dose and 15.35 ± 8.44 for the high dose. After 6 months, the scores were 14.08 ± 10.30 for the low dose and 12.46 ± 6.38 for the high dose, indicating that both dosages of P. mirifica were similarly effective and safe in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. There were no significant adverse effects seen at either dose. [13]

Red clover contains phytoestrogens, substances that have a similar effect to estrogens, and also contains isoflavones. Scientific evidence to date does not support red clover helping to relieve menopausal transition symptoms like hot flashes.[3] In a different study on menopausal transition quality of life, treatment with red clover supplements showed no comparable difference to treatment with a placebo. [9] There is also little research on the possible side effects of red clover.

Siberian rhubarb is used both as a food and also as a medicinal plant, where it is used to treat constipation, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal complaints. It has laxative qualities that are similar to extracts from senna plants. Siberian rhubarb contains two hydrostilbenes, rhapontigenin and desoxyrhapontigenin, both of which show binding affinity for the estrogen receptors ER-α and ER-β. Studies in the lab and on humans indicate that hydrostilbenes in rhubarb act as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) with mixed agonist/antagonist activity.[2]

There is one commercial preparation of rhubarb extract called Estrovera that contains a proprietary extract called “rhaponticin” or “extract ERr 731.” One study randomized 109 symptomatic perimenopausal women to treatment with either one tablet of ERr 731 or a placebo daily for 12 weeks. Only 46 of the 109 women completed the study, impacting the strength of the results. Despite this the results at 12 weeks showed the Menopause Rating Scale II total score, and each symptom within the scale had significantly improved in the active-treatment group versus placebo.[2] Few negative effects have been reported but more research is needed to further explore both the usefulness and the safety of Siberian rhubarb.

Wild yam is a tuber that contains diosgenin, a steroid precursor used in the manufacture of synthetic steroids. In the lab, diosgenin can be converted into progesterone, but this conversion does not happen naturally in humans or other living animals. It is commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine for multiple symptoms including those of menopausal transition.

Alternative medicine practitioners suggest that substances in the wild yam can stimulate the natural production of sex hormones, including estrogen and progesterone. One study showed that substituting one type of wild yam (D. alata) for other carbohydrates twice daily for 30 days in the diets of 24 Japanese women, the women showed a significant increase in serum concentrations of estrone (26%) and sex hormone-binding globulin (9.5%) and a near-significant increase in estradiol (27%). The control group, 19 women fed plain sweet potatoes, did not show this effect.[2] A different study showed that wild yam cream was no better than a placebo in reducing menopausal transition symptoms or increasing levels of estrogen and progesterone. [8]

One RCT of 50 women who consumed 12 mg of Dioscorea alata extract twice daily reported significant improvements (90%) in menopause symptoms (primarily psychological) compared with the placebo group (70%) as measured by the Greene Climacteric Scale.[8]

Evidence supporting the use of wild yam for vasomotor symptoms is limited. One clinical trial employing a yam cream to treat menopausal transition symptoms reported no significant benefit, however it should be noted that many yam creams have been shown to contain no actual yam extract, and in fact many have had steroids, including estrogens, progesterone, and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) added to them. This, added to the lack of scientific evidence for wild yam effectiveness in treating vasomotor symptoms, indicates that yam creams are not recommended for use in treating these symptoms. [2]

Myths & Mysteries

MYTH

The majority of ‘natural’ products and remedies appear to be safe, but, for the most part, they haven’t usually been examined using rigorous scientific methods, so little if any information is available about side effects, toxicity and interactions with other drugs. Consider the fact that foxglove, poison ivy and coral snake venom are examples of completely natural products, but (hopefully) you wouldn’t consider them safe to use in any way!

MYTH

‘Natural’ has no regulatory meaning. This means that products claiming to be all-natural have not been subjected to the rigorous scrutiny about safety and effectiveness that pharmaceutical products have been. Make sure you track the changes in your symptoms as well as any potential side-effects you feel when taking “natural” supplements to make sure they are not actually making things worse. We are not talking about fresh mint tea here, we are talking about plant derivatives that have claims associated with them that may or may not be founded in reality.

MYTH

As with safety information for natural products, herbal remedies haven’t usually been examined using rigorous scientific methods, so little if any information is on their effectiveness. Make sure you track the changes in your symptoms as well as any potential side-effects you feel when taking “natural” supplements to make sure they are not actually making things worse. We are not talking about fresh mint tea here, we are talking about plant derivatives that have claims associated with them that may or may not be founded in reality.

MYSTERY

The placebo effect occurs when a treatment or remedy has a beneficial effect for no scientifically supported reason. Placebos are regularly used in research studies as a control group relative to the active treatment. The placebo effect, when the placebo has the same effect as the treatment, is still poorly understood by the scientific community, but there is no doubt that it is real and can be powerful.

MYTH

Some provinces and states do have a regulatory body for naturopaths with certain training and credentials. However, even in these regions, anyone can call themselves a naturopath and begin practicing, even though there is no oversight on how they conduct themselves or whether they are providing safe, high quality care.

MYTH

Naturopathic physicians, also known as naturopathic doctors (ND) or doctors of naturopathic medicine (NMD) have training at an accredited four-year graduate level program. The training they receive is similar to conventional medical training, with additional training in nutrition, psychology and alternative (also called complementary) therapies including herbal medicines. NDs and NMDs are regulated in many provinces and states, and in some, they have the ability to write prescriptions. Naturopaths are not formally trained in any programs nor can they be licenced or prescribe medicines.

MYTH

While many naturopaths are homeopaths, not all homeopaths are naturopaths. Homeopathic practitioners use only homeopathic remedies, which are made from diluted natural substances. Naturopathic practitioners may use herbal remedies, nutrition and lifestyle adjustments, and natural supplements. Naturopathic doctors (ND) or doctors of naturopathic medicine (NMD) may also prescribe medicines.

MYTH

Holistic medicine is not a stand-alone type of medicine, rather it is an approach to treatments. Naturopathy is not guaranteed to be holistic, but in reality, most naturopaths practice holistic medicine, where the treatments are focused on the interconnected relationships amongst mind, body and spirit. As well, many western medicine practitioners are also holistic in their approach.

Compiled References

[1] De Franciscis P, Colacurci N, Riemma G, et al. A Nutraceutical Approach to Menopausal Complaints. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(9):544. Published 2019 Aug 28. doi:10.3390/medicina55090544

[2] Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms, Menopause: November 2015 – Volume 22 – Issue 11 – p 1155-1174 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000546

[3] InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Relieving menopause symptoms on your own. [Updated 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279307/

[4] Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015 Nov;22(11):1155-72; quiz 1173-4. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000546. PMID: 26382310.

[5] Kligler B. Black cohosh. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Jul 1;68(1):114-6. PMID: 12887117.

[6] Ruhlen RL, Sun GY, Sauter ER. Black Cohosh: Insights into its Mechanism(s) of Action. Integr Med Insights. 2008;3:21-32

[7] Leach MJ, Moore V. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga spp.) for menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(9):CD007244. Published 2012 Sep 12. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007244.pub2

[8] Johnson A, Roberts L, Elkins G. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Menopause. J Evid Based Integr Med. 2019;24:2515690X19829380. doi:10.1177/2515690X19829380

[9] Ehsanpour S, Salehi K, Zolfaghari B, Bakhtiari S. The effects of red clover on quality of life in post-menopausal women. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17(1):34-40.

[10] Erkkola R, Vervarcke S, Vansteelandt S, Rompotti P, De Keukeleire D, Heyerick A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot study on the use of a standardized hop extract to alleviate menopausal discomforts. Phytomedicine. 2010 May;17(6):389-96. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.01.007. Epub 2010 Feb 18. PMID: 20167461.

[11] Lee MS, Shin BC, Yang EJ, Lim HJ, Ernst E. Maca (Lepidium meyenii) for treatment of menopausal symptoms: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2011 Nov;70(3):227-33. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.07.017. Epub 2011 Aug 15. PMID: 21840656.

[12] Yang HM, Liao MF, Zhu SY, Liao MN, Rohdewald P. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on the effect of Pycnogenol on the climacteric syndrome in peri-menopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(8):978-85. doi: 10.1080/00016340701446108. PMID: 17653885.

[13] Virojchaiwong P, Suvithayasiri V, Itharat A. Comparison of Pueraria mirifica 25 and 50 mg for menopausal symptoms. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011 Aug;284(2):411-9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1689-5. Epub 2010 Sep 26. PMID: 20872225.

[14] Naseri R, Farnia V, Yazdchi K, Alikhani M, Basanj B, Salemi S. Comparison of Vitex agnus-castus Extracts with Placebo in Reducing Menopausal Symptoms: A Randomized Double-Blind Study. Korean J Fam Med. 2019 Nov;40(6):362-367. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.18.0067. Epub 2019 May 9. PMID: 31067851; PMCID: PMC6887765.

[15] Chinnappan SM, George A, Evans M, Anthony J. Efficacy of Labisia pumila and Eurycoma longifolia standardised extracts on hot flushes, quality of life, hormone and lipid profile of peri-menopausal and menopausal women: a randomised, placebo-controlled study. Food Nutr Res. 2020 Sep 3;64. doi: 10.29219/fnr.v64.3665. PMID: 33061884; PMCID: PMC7534949.

[16] Zohreh Saberi, Narjes Gorji, Zahra Memariani, Reihaneh Moeini, Hoda Shirafkan, Mania Amiri. Evaluation of the effect of Silybum marianum extract on menopausal symptoms: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Phytotherapy Research. 2020 Dec V34(12) 3359-3366. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6789