Menopause and Hormone Therapy

Your body has preferred levels of hormones that allow it to function at its best. It is normal for hormone levels to change as you age, but sometimes the change in the female hormone cycle can cause symptoms that affect your quality of life.

What are the Main Types of Hormone Therapy?

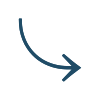

There are multiple types and delivery methods for hormone therapy. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) has published a document outlining hormone therapy products approved and available for use in Canada.[19] A summary table can be found here

What are the Issues with Hormone Therapies and Menopause?

The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) declares that Menopause Hormone Therapy (MHT) remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture.

The risks of MHT differ depending on which type of MHT is prescribed as well as the dose and the length of time the MHT is taken. When MHT starts and whether or not a progestogen is used also affects risk. [2]

Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Menopausal Transition Symptoms

MHT has been shown to assist with hot flashes, night sweats, bone loss and fracture, vaginal dryness and urinary incontinence. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) position statement [2] [8] and other research [4] [5] [6] [9] [10] provide information specific to different symptoms of the menopausal transition.

Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Women’s Health

Hormone therapy is an excellent therapy for the treatment of many women’s menopausal transition symptoms. However, hormone therapy has effects in the body beyond just bothersome symptoms.

What is Bioidentical Hormone Therapy?

Bioidentical hormones are synthetic compounds that are manufactured to mimic natural hormones. They are intended to interact with hormone receptors in the body in the same way as natural, or conventional, hormones. [2] [4] [15]

Menopause and Hormone Therapy

Your body has preferred levels of hormones that allow it to function at its best. It is normal for hormone levels to change as you age, but sometimes the change in the female hormone cycle can cause symptoms that affect your quality of life. When you are experiencing symptoms throughout your menopause transition you may be referred to an endocrinologist (a doctor who specializes in hormones and the glands that produce them) – if not, you may request to see one by asking your healthcare provider.

Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) such as hot flashes and night sweats, and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture. The risks of hormone therapy differ for women, and depend on type, dose, duration of use, route of administration, timing of initiation, and whether a progestogen, which is a class of steroid hormones, is needed.

It is very important to understand the difference between MHT use in women with a uterus compared to women without a uterus.

If the woman has a uterus, she should receive a combined estrogen plus progestin treatment to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer). Treatment should be tailored to the individual in partnership with their healthcare provider to make sure the treatment maximizes benefits and minimizes risks.

It is very important to understand the difference between MHT use in women with a uterus compared to women without a uterus. Estrogen alone (referred to as unopposed estrogen or ET for estrogen therapy) is used in MHT when a woman has had a hysterectomy and no longer has a uterus. If a woman still has a uterus, her MHT must include both estrogen and progestin (a hormone that mimics natural progesterone). MHT with estrogen and progestin is called EPT.

In the uterus, estrogen alone can promote a pre-cancerous condition called endometrial hyperplasia. This is an overgrowth of the normal tissue in the uterine lining, causing it to thicken, and causing abnormally heavy menstrual bleeding. An early landmark study looked at the relationship between estrogen use and endometrial cancer and found that there was a 6 times likelihood of endometrial cancer for women with a uterus using estrogen-only therapy. The risk increased to 15 times more likely if estrogen was used long-term (greater than 5 years). This risk is drastically reduced if progesterone in any form is used with estrogen in the MHT. [1]

Your healthcare provider is the best source to advise you on whether or not this therapy will improve your quality of life. To get MHT, you will need a prescription from a medical doctor (General Practitioner (GP), Obstetrician-Gynecologist (OB/GYN), or an endocrinologist), nurse practitioner, or, in some places, a naturopathic doctor (ND).

If you do not already have a healthcare practitioner who is familiar with identifying and treating symptoms of menopause, the North American Menopause Society provides a list of menopause practitioners at https://portal.menopause.org/NAMS/NAMS/Directory/Menopause-Practitioner.aspx

It is highly recommended that women considering MHT have a thorough discussion with their health care provider about their specific symptoms and what help they are looking for .

- Track your symptoms: Before and after your MHT medication, did your symptoms go up or down over time? Any new ones come up? A simple notebook and pencil will help to track the date and record how you felt at that time. Share this with your health care provider to make your appointments more effective and efficient.

- More is not better: The goal of MHT is to use the lowest, most effective dose of hormone therapy that provides benefit while minimizing risk. This means that the form it comes in, the dose, and how you take the drugs should be determined individually and reassessed periodically.

- Understand the risks: Potential risks of MHT for women aged younger than 60 years or who are within 10 years of menopause onset (around the age of 40) include the rare risk of breast cancer with combined estrogen-progestogen therapy (EPT), thickening of the uterine lining (endometrial hyperplasia), and cancer (when there is too much estrogen with no progestogen), blood clots, and gallbladder issues. [2] Different hormone therapies may have different effects on target organs, so know that there are options available to minimize risk. Additional risks across ages include heart attack, stroke, and dementia. [2]

Women with early or premature natural menopause (when periods stop before the age of 40) and Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (POI – a condition where the ovaries stop working properly for no obvious medical reason) experience an extended period of time without ovarian hormone activity leading to a potential estrogen deficiency in all tissues compared with women experiencing normal menopause.

Health risks of early natural menopause and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) may include persistent vasomotor symptoms (VMS – hot flashes and night sweats), bone loss, genitourinary syndrome, mood changes, and increased risk of heart disease, dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, eye disorders, and overall mortality.[2] As well, women with POI have a higher risk of death from ischemic heart disease (heart disease caused by narrowed arteries) as well as from all causes, compared with women who have a normal age of natural menopause, which may be reflective of premature reproductive aging. They also have a higher risk of digestive tract cancer but a decreased risk of mortality from breast, uterine, and endometrial cancer. [2]

- Effective management may include appropriate doses of MHT along with calcium, vitamin D, exercise, and screenings to detect medical issues.

- Hormone therapy is recommended at least until the average age of menopause (approximately age 52 y), with an option for use of oral contraceptives in healthy younger women, unless there are other health issues that will be negatively affected by MHT.

- Results of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) studies in older women [3] do not apply to women with early menopause. [2]

- Fertility preservation and counseling should be explored for young women at risk for POI.

- Keeping the ovaries is recommended when hysterectomy is performed to treat benign conditions in premenopausal women at average risk for ovarian cancer.

When both ovaries are surgically removed (bilateral oophorectomy), the loss of ovarian hormones – estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone – is abrupt. This can trigger vasomotor symptoms as well as a variety of estrogen deficiency-related symptoms and diseases that can have a major effect on quality of life (QOL). You can assess your own Quality of Life here [Link to resources section].

- Potential adverse events (AEs) can occur in the cardiovascular system, and on bone health, mood, sexual health, and cognition. All of these have been shown (in clinical observational studies) to be improved by MHT. [2]

- In women with both ovaries and uterus removed before the average age of menopause, starting MHT therapy early reduces VMS, genitourinary symptoms, risk for osteoporosis and related fractures, cardiovascular disease and overall mortality. If the uterus is not removed, MHT must include both estrogen and progestin to protect against endometrial cancer.

- Observational data suggest that there is also a benefit by reducing the occurrence of atherosclerosis (hardening or thickening of the arteries) and other cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline and dementia.

- Younger women may require higher doses for symptom relief and/or protection against bone loss.

What are the Main Types of Hormone Therapy?

There are multiple types and delivery methods for hormone therapy. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ of Canada (SOGC) has published a document outlining hormone therapy products approved and available for use in Canada.[1] A summary table is shown below.

What types of MHT are there?

Hormone therapy is prescribed as either systemic MHT (throughout the body) or low-dose vaginal MHT.

- Systemic estrogen comes in many forms (e.g. cream, tablets, skin patches etc.) and typically contains a higher dose of estrogen that is absorbed throughout the body.

- Systemic MHT is prescribed for vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats)

- Low-dose vaginal MHT comes in multiple forms (cream, tablet, or insertable vaginal ring) and minimizes the amount of estrogen absorbed by the body. Low-dose vaginal MHT is only used to treat the vaginal and urinary symptoms of menopause.

- Low-dose vaginal MHT is prescribed for vaginal dryness and urinary problems (these symptoms combined are called the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause or GSM).

There are a variety of hormones used in MHT including estrogen alone (estrogen therapy or ET), using multiple types of estrogens, or using a mix of estrogen and progesterone (estrogen and progestogen therapy or EPT) in multiple combinations. In addition to estrogen or estrogen-progestogen combinations, other MHT treatments include the use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) to make tissue-selective estrogen complexes (TSECs). [2] Note that progesterone is difficult to absorb orally, so synthetic forms – both progestogen (a natural hormone) and progestin (an equivalent synthetic hormone) are used in MHT.

What are the Issues with Hormone Therapies and Menopause?

The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) declares that Menopause Hormone Therapy (MHT) remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture.

The risks of MHT differ depending on which type of MHT is prescribed as well as the dose and the length of time the MHT is taken. When MHT starts and whether or not a progestogen is used also affects risk. [2]

MHT has been helping women with their perimenopausal symptoms for over 80 years with the first hormone therapy used specifically to treat symptoms of the menopausal transition happening in 1942. By the 1960s, estrogen was considered a ‘vital substance’ for all women and was prescribed broadly.

This all changed in 2002, when the first set of results from the Women’s Health Initiative study were published. These results showed that post-menopausal women taking combination (estrogen and progestin) hormone therapy for menopause symptoms had an increased risk for breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, blood clots, and urinary incontinence. While the results were accurate for the group under study (women aged 50-79), this is not the age group that is typically considered to start hormone therapy.

In fact, there were limited study participants with bothersome menopausal transition symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) who were younger than 60 years old or who were fewer than 10 years from the onset of menopause; this is the group for whom hormone therapy is usually indicated. The study design assessed ‘Does hormone therapy help prevent coronary artery disease?’, and used one group to investigate one type of estrogen/progesterone treatment and another group to investigate an estrogen-only treatment. While the study results themselves were accurate, the results were applied far too broadly, well beyond the scope of the study. [6]

This triggered an undeserved reputation for serious side effects from MHT, causing an 80%+ decline in the prescription of hormone therapy and created fear and uncertainty that exist into the present day. [3] The reduction in hormone therapy prescriptions was a direct result of the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) warning labels that were issued for ‘all women and pertaining to all estrogens and progestogens, and to all doses and routes of administration’, an inaccurate conclusion based on the study results. [6]

Work to accurately communicate results of hormone therapy studies continues to the present day. Worldwide, there has been a shift to develop updated recommendations. For example, the updated 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) provides more accurate recommendations. [2] [8] An advisory panel of clinicians and researchers with expertise in women’s health and menopause assessed the WHI paper as well as all subsequently published research to develop the updated position statement, which reads:

- Menopause Hormone Therapy (MHT) remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture. The risks of MHT differ depending on type, dose, duration of use, route of administration, timing of initiation, and whether a progestogen is used. Treatment should be individualized to identify the most appropriate MHT type, dose, formulation, route of administration, and duration of use, using the best available evidence to maximize benefits and minimize risks, with periodic reevaluation of the benefits and risks of continuing or discontinuing MHT.

- For women under 60 years old or who are within 10 years of menopause onset and have no contraindications, the benefit-risk ratio is most favorable for treatment of bothersome VMS and for those at elevated risk for bone loss or fracture.

- For women who initiate MHT more than 10 or 20 years from their menopause onset or are over 60 years old, the benefit-risk ratio appears less favorable because of the greater absolute risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism (blood clots), and dementia.

- Longer durations of therapy should be for documented indications such as persistent VMS or bone loss, with shared decision making and periodic reevaluation. For bothersome GSM symptoms not relieved with over-the-counter therapies and without indications for use of systemic MHT ,low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy or other therapies are recommended.

The full position statement can be found at http://www.menopause.org/ [2]

Despite the warning labels included in all prescriptions, the FDA currently approves hormone therapy for:

- bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS);

- prevention of bone loss;

- hypoestrogenism (low estrogen) caused by hypogonadism (low to no production of sex hormones), oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries), or Primary Ovarian insufficiency (POI – when the ovaries stop working properly); and

- genitourinary symptoms (vaginal dryness, painful sex, incontinence etc.).

Safety of using MHT can be assessed using both relative and absolute risk. Relative risk (also called the risk ratio) compares the odds of an event happening to two groups by comparing them against each other. For example, if you look at two groups of women – one with a mother, sister or daughter who has had breast cancer and the other without any close female relatives with breast cancer – the relative risk of breast cancer is higher in the group with close female relatives that have breast cancer.

Relative risk doesn’t give information on a woman’s actual odds, or absolute risk, of getting breast cancer. The newly released updated 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) indicates the following about MHT safety:

- Increased absolute risks associated with estrogen-progestogen therapy (EPT) and estrogen-alone therapy (ET) are rare (<10/10,000/y). These increased risks are for blood clots (venous thromboembolism) and gallbladder disease.

- There is a rare increased risk for stroke and breast cancer with EPT. If ET is used alone in women with a uterus, there is an increased risk of thickening of the uterine lining (endometrial hyperplasia) and endometrial cancer.

- There is a reduced absolute risk for all-cause mortality, bone fractures, diabetes mellitus (using both EPT and ET), and breast cancer (using ET) in women aged younger than 60 years as shown in the graph. [2]

Decisions about how long to stay on MHT are difficult because the long-term follow-up data is complicated to interpret, especially with respect to breast cancer. However, NAMS states with confidence that:

- The benefits of MHT include relief of persistent vasomotor symptoms, prevention of bone loss and fracture, and prevention or treatment of GSM.

- Concerns include potential risk of breast cancer that may increase with longer duration of use.

- Coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality may be decreased when MHT is initiated closer to menopause onset, with fewer heart attacks occurring with estrogen-only MHT.

- Women who initiate MHT when aged older than 60 years or who are more than 10 years from the onset of menopause are at higher absolute risks of coronary heart disease, blood clots, and stroke than women initiating MHT in early menopause.

- More research is needed on benefits and risks of longer durations of use and potential benefits and risks with discontinuation. [2]

In July 2022, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) released an update to the 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement. Read more about the updated statement here.

In June 2023, NAMS released a position statement on non-hormone alternatives to MHT to provide evidence-based guidance that can prevent the use of inappropriate or ineffective therapies and to support the use of effective ones. However, hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms.

Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Menopausal Transition Symptoms

MHT has been shown to assist with hot flashes, night sweats, bone loss and fracture, vaginal dryness and urinary incontinence. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) position statement [2] [8] and other research [4] [5] [6] [9] [10] provide the following information specific to different symptoms of the menopausal transition:

According to the International Menopause Society, MHT remains the most effective therapy for hot flashes and night sweats and it is well documented that the frequency and intensity of hot flashes and night sweats can be reduced by estrogen MHT. [2][4]

- Hormone therapy remains the gold standard for relief of VMS.

- Estrogen-alone therapy (ET) can be used for symptomatic women without a uterus.

- For symptomatic women with a uterus, EPT or a tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) protects against endometrial neoplasia.

- Micronized progesterone 300 mg nightly significantly decreases VMS (hot flashes and night sweats) compared with placebo and improves sleep. Micronized means the particle size has been reduced making it easier to absorb into the body. However, no long-term study results are available. Using any form of progestogens (such as the synthetic progestin) without estrogen for hot flashes or night sweats is not medically approved.[2]

During the menopause transition, women with vasomotor symptoms are more likely to report reduced sleep. Hormone therapy has been shown to improve sleep in women with bothersome night time VMS by reducing night time awakenings. [2][6][9]

- Hormone therapy improves sleep in women with bothersome nighttime VMS by reducing nighttime awakenings. Estrogen may have some effect on sleep, independent of VMS. [2]

- Natural progesterone in 300 mg doses at bedtime has been shown to help sleep. [20]

Vaginal symptoms of GSM may include genital dryness, burning, and irritation and sexual symptoms of diminished lubrication and painful intercourse. [2]

- Low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations are effective and generally safe for the treatment of GSM, with minimal absorption throughout the body. It is preferred over systemic (body-wide) therapies when estrogen therapy is only being used for treatment of GSM symptoms.

- For women with breast cancer, low-dose vaginal estrogen should be considered and prescribed in consultation with their oncologists.

- Progestogen therapy is not needed with low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy, but randomized trial data are lacking beyond 1 year study durations.

- Non-estrogen prescription FDA-approved therapies that improve vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) in postmenopausal women include ospemifene and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which has been recently approved for use by Health Canada.

- If you experience vaginal bleeding post menopause (after your periods have stopped for one full year or more), insist on receiving further tests or care. This is not normal.

Urinary tract symptoms of GSM include pelvic floor disorders (prolapse), urinary symptoms of urgency, incontinence, painful urination, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).

- Systemic hormone therapy does not improve urinary incontinence and may increase the incidence of stress urinary incontinence.

- Low-dose vaginal ET may help with urinary symptoms, including prevention of recurrent UTIs, overactive bladder, and urge incontinence.

- Hormone therapy is not FDA approved for any urinary health indication.

Systemic MHT and low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy may be effective for treatment of sexual problems by increasing lubrication, blood flow, and sensation in vaginal tissues. If sexual problems, including sexual interest, arousal, and orgasmic response are not caused by menopausal transition symptoms (such as decreased lubrication that causes painful intercourse) then MHT or low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy will not help. [2]

- Low-dose vaginal ET improves sexual function in postmenopausal women with GSM. Both systemic MHT and low-dose vaginal estrogen increase lubrication, blood flow, and sensation of vaginal tissues.

- Systemic hormone therapy generally does not improve sexual function, sexual interest, arousal, or orgasmic response beyond its effect on genitourinary symptoms (GSM). If sexual function or libido are concerns in women with menopause symptoms, using transdermal MHT may be a better choice than oral MHT because it has a smaller effect on molecules (sex hormone-binding globulin and free testosterone) that impact sexual function and libido.

- Non-estrogen alternatives approved by the FDA for painful intercourse include ospemifene and intravaginal DHEA.

Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Women’s Health

Hormone therapy is an excellent therapy for the treatment of many women’s menopausal transition symptoms. However, hormone therapy has effects in the body beyond just bothersome symptoms. The impacts of MHT on various body systems and health conditions are detailed below.

One review study showed that hormone therapy provides a significant benefit for menopause-specific quality of life in midlife women, mainly through relief of symptoms. Treatment can also cause an increase in the overall quality of life. [11] Women who experience severe symptoms tend to experience statistically significant improvement in both health-related and menopause-specific quality of life measures. Similar levels of improvement are not shown to be statistically significant for women who do not experience severe symptoms as measured during clinical trials.[11] Another review study also concluded that MHT improves quality of life of symptomatic menopausal women. This study also found reliable evidence on quality of life improvements beyond just a reduction in vasomotor symptoms.[12]

Visit our resources page here to find the tools to assess your Quality of Life.

Standard-dose ET and MHT prevent bone loss in postmenopausal women by inhibiting bone resorption, which is the process by which osteoclasts (a type of bone cell) break down the tissues making up bones and release those minerals causing a transfer of calcium from bone tissue to the blood. The estrogen in MHT is highly effective at preventing menopause-related bone loss. [2][6]

- Hormone therapy prevents bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women, with dose-related effects on bone density.

- Hormone therapy reduces fracture risk in healthy postmenopausal women.

- Discontinuing hormone therapy results in rapid bone loss; however, no excess in fractures was seen in the WHI after discontinuation of MHT.

- Hormone therapy is FDA approved for prevention of bone loss, but not for treatment of osteoporosis.

- In women aged younger than 60 years or within 10 years of menopause onset, systemic hormone therapy is an appropriate therapy to protect against bone loss, unless there are other health reasons to avoid MHT.

- Women with premature menopause without prior fragility fracture or osteoporosis are best served with hormone therapy or oral contraceptives to prevent bone density loss and reduce fracture risk, rather than other bone-specific treatments, until the average age of menopause, when treatment may be reassessed.

- Decisions regarding initiation and discontinuation of hormone therapy should be made primarily on the basis of non-bone related benefits (ie, reduction of VMS) and risks.

Hormone therapy can be used to manage symptoms that affect the skin, hair, sight, hearing and balance. [2]

- Estrogen therapy appears to have beneficial effects on skin thickness and elasticity and collagen when given at menopause.

- Changes in hair density and female pattern hair loss worsen after menopause, but research is lacking regarding a role for hormone therapy in mitigating these changes.

- Hormone therapy appears to decrease the risk of age-related macular degeneration but not early or late-stage macular degeneration.

- Estrogen therapy appears to reduce the pressure inside the eye (intraocular pressure) and mitigate the risk for some types of open-angle glaucoma in Black women.

- Evidence of hormone therapy effects on cataracts, optic nerve disease, dry-eye disease, and hearing loss is mixed.

- Little is known about hormone therapy effects on olfactory changes.

- In small trials, hormone therapy appears to decrease dizziness or vertigo and improve postural balance.

Hormone therapy containing estrogen can be beneficial for joint pain. Direct binding of estrogen to estrogen receptors in joint tissues protects the biomechanical structure and function and helps maintain overall joint health. [2]

- Women in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and other studies have shown less joint pain or stiffness on MHT compared with those on placebo.

- There is a need for further understanding of estrogen’s potential effect on joint health.

Sarcopenia, the loss of muscle as you age, results in frailty and is associated with adverse events such as falls, hospitalization, disability, and death. While skeletal muscle does contain estrogen receptors, little is known about the interactions between estrogen and muscle.

- Sarcopenia and osteoporosis are related to aging, estrogen depletion, and the menopause transition.

- Development of frailty with aging is a health risk.

- Intervention to improve energy exchanges (bioenergetics) and prevent loss of muscle mass, strength, and performance is needed.

- Preclinical studies suggest a possible benefit of ET when combined with exercise to prevent the loss of muscle mass, strength, and performance.

- Risk of gallstones, inflammation of the gallbladder, and the need to surgically remove the gallbladder is increased with oral estrogen-alone and combination MHT.

- Observational studies report lower risk of gallstones with transdermal hormone therapy than with oral, and with oral estradiol compared with CEE, but neither observation is confirmed in RCTs.

- In women with hepatitis C and with fatty liver, a slower fibrosis progression has been observed with use of hormone therapy, but RCTs are needed to establish the potential benefits and risks with liver disease.

- Hormone therapy significantly reduces the diagnosis of new-onset type 2 diabetes, but it is not currently FDA approved for this purpose.

- Hormone therapy is appropriate in otherwise healthy women with pre-existing type 2 diabetes and may help control blood sugars when used for menopause symptom management.

- Although hormone therapy may help reduce the accumulation of fat around the abdomen and weight gain associated with the menopause transition, the effect is small.

- There is some evidence that ET has antidepressant effects similar to those observed with antidepressant agents when administered to depressed perimenopausal women with or without VMS symptoms.

- Estrogen therapy is ineffective as a treatment for depressive disorders in postmenopausal women. This suggests there is a possible ‘window of opportunity’ for the effective use of ET to manage depressive disorders during the menopausal transition.

- There is some evidence that ET enhances mood and improves well-being in nondepressed perimenopausal women.

- Transdermal estradiol with micronized progesterone may prevent the onset of depressive symptoms in non-depressed perimenopausal women, but the evidence is not sufficient to recommend estrogen-based therapies for preventing depression in asymptomatic perimenopausal or postmenopausal women. The risks and benefits must be weighed carefully.

- Estrogen-based therapies may be used in addition to antidepressants in midlife and older women, preferably when also indicated for other menopause symptoms such as VMS.

- Most studies on hormone therapy for the treatment of depression examined the effects of unopposed estrogen. Data on EPT or for different progestogens are sparse and inconclusive.

- Estrogen is not government approved to treat mood disturbance.

- Based on current research, hormone therapy is not recommended at any age to prevent or treat a decline in cognitive function or dementia.

- Initiating hormone therapy in women aged older than 65 years increases the risk for dementia, with an additional 23 cases per 10,000 person-years seen in women randomized to CEE plus MPA in the WHI Memory Study. [13]

- The effect of hormone therapy may be impacted by initial cognitive function, with more favorable effects in women with normal cognitive function before starting hormone therapy.

- Estrogen therapy may have cognitive benefits when initiated immediately after hysterectomy with removal of both ovaries, but hormone therapy in the early natural post menopause period has neutral effects on cognitive function.

- Observational data and reanalysis of older studies by age or time since menopause, including the WHI, suggest that for healthy, recently menopausal women, the benefits of MHT (estrogen alone or with a progestogen) outweigh its risks, with fewer cardiovascular events in younger versus older women.

- For healthy symptomatic women aged younger than 60 years or within 10 years of menopause onset, the positive effects of hormone therapy on CHD and all-cause mortality should be considered against potential rare increases in risks of breast cancer, blood clots, and stroke.

- Hormone therapy is not government approved for protection of the cardiovascular system.

- Personal and familial risk of CVD, stroke, blood clots, and breast cancer should be considered when initiating hormone therapy.

- The effects of hormone therapy on CHD may vary depending on when hormone therapy is initiated in relation to a woman’s age or time since menopause onset.

- Initiation of hormone therapy in recently postmenopausal women reduced or had no effect on the progression of hardening and calcification of the arteries (atherosclerosis) in randomized, controlled trials.

- Observational data and meta-analyses show reduced risk of CHD in women who start hormone therapy when aged younger than 60 years or within 10 years of menopause onset. Meta-analyses show no impact of hormone therapy on CHD after excluding open-label trials, or trials where patients and healthcare providers know what treatment is being given (most clinical trials are ‘blind’ or ‘double-blind’ where neither the patient or healthcare provider is aware which treatment is being used).

- Women who initiate hormone therapy aged older than 60 years or more than 10 or 20 years from menopause onset are at higher absolute risks of CHD, VTE, and stroke than women initiating hormone therapy in early menopause.

Different types of estrogen may have different effects on the breast so the results of studies are limited and they should not be generalized. The type and severity of breast cancer risk from MHT varies depending on the type of MHT, the dosage, the duration of the treatment, the time the treatment is initiated and individual patient characteristics.

-

- The risk of breast cancer related to hormone therapy use is low, with estimates indicating a rare occurrence – less than one additional case per 1,000 women per year of hormone therapy use or three additional cases per 1,000 women when used for 5 years with CEE plus MPA (conjugated equine estrogens plus progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate).

-

- Women should be counseled about the risk of breast cancer with hormone therapy, putting the data into perspective, with risk similar to that of modifiable risk factors such as two daily alcoholic beverages, obesity, and low physical activity.

-

- The effect of hormone therapy on breast cancer risk may depend on the type of hormone therapy, duration of use, regimen, prior exposure, and individual characteristics.

-

- Different hormone therapy regimens may be associated with increased breast density, which may obscure mammographic interpretation, leading to more mammograms or more breast biopsies and a potential delay in breast cancer diagnosis.

-

- A large quantity of data does not show an additive effect of underlying breast cancer risk (age, family history of breast cancer, genetic risk of breast cancer, benign breast disease, personal breast cancer risk factors) and hormone therapy use on breast cancer incidence.

-

- Observational evidence suggests that hormone therapy use does not further increase risk of breast cancer in women at high risk because of a family history of breast cancer.

-

- Systemic hormone therapy is generally not advised for survivors of breast cancer, although hormone therapy use may be considered in women with severe VMS that does not respond to non hormonal options. This decision should be shared with a woman’s oncologist.

-

- For survivors of breast cancer with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), low-dose vaginal ET or DHEA may be considered in consultation with their oncologists if bothersome symptoms persist after a trial of nonhormone therapy.

-

- Regular breast cancer surveillance is advised for all postmenopausal women based on current breast cancer screening guidelines, including those who use hormone therapy.

- Unopposed systemic ET (estrogen without opposing progestogen) in a postmenopausal woman with an intact uterus increases the risk of endometrial cancer, so adequate progestogen is recommended. [1]

- Low-dose vaginal ET does not appear to increase endometrial cancer risk, although trials with endometrial biopsy end points are limited to 1 year in duration.

- Use of hormone therapy is an option for the treatment of bothersome menopause symptoms in women with surgically treated, early stage, low-grade endometrial cancer in consultation with a woman’s oncologist if non hormonal therapies are ineffective.

- Systemic hormone therapy is not advised with high-grade, advanced-stage endometrial cancers or with endometrial stromal sarcomas or leiomyosarcomas.

- Use of oral contraceptives is associated with a significant reduction in ovarian cancer risk.

- Current and recent use of hormone therapy is associated with a small but statistically significant risk of ovarian cancer in observational studies, principally for serous type, although there was no increase in ovarian cancer risk in women randomized to estrogen + progestogen therapy (EPT) in the WHI.

- In women with a history of ovarian cancer, benefits of hormone therapy use generally outweigh risks, especially with bothersome VMS or during early menopause; use of hormone therapy is not advised in women with hormone-dependent ovarian cancers, including granulosa-cell tumors and low-grade serous carcinoma.

- Short-term hormone therapy use appears safe in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic variants who undergo risk-reducing surgery to remove both ovaries and fallopian tubes (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or BSO) before the average age of menopause.

- Observational studies suggest a reduced incidence of colorectal cancer in current hormone therapy users, with reduced mortality.

- In the WHI, EPT, but not ET alone, reduced colorectal cancer risk, although cancers diagnosed in EPT users were diagnosed at a more advanced stage. There was no difference in colorectal cancer mortality with either EPT or ET.

- There appears to be an overall neutral effect of hormone therapy on lung cancer incidence and survival.

- Quitting smoking should be encouraged, with increased lung cancer surveillance for older smokers, including current or past users of hormone therapy.

Duration of Use, Initiation After Age 60 years, and Discontinuation of Hormone Therapy

The benefits of hormone therapy outweigh the risks for healthy women with bothersome menopause symptoms who are aged younger than 60 years or within 10 years of menopause onset. However, the risk of MHT does increase the older women are and the longer MHT is used. As such, women are advised to use the appropriate dose for the time needed to manage their symptoms. Many women experience bothersome symptoms for many years, so long-duration hormone therapy use may be needed. This should be assessed on an individual basis, so creating arbitrary age-based guidance on when to stop using MHT is not clinically appropriate.

- The safety profile of hormone therapy is best when it is started in healthy women aged younger than 60 years or within 10 years of menopause onset. Starting hormone therapy by menopausal women aged older than 60 years requires careful consideration of individual benefits and risks.

- Long-term use of hormone therapy, including for women aged older than 60 years, may be considered in healthy women at low risk of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer if they are experiencing persistent VMS or are at an elevated risk of fracture, if other therapies are not appropriate.

- Factors that should be considered include severity of symptoms, effectiveness of alternative non hormonal interventions, and underlying risk for osteoporosis, coronary heart disease, loss of blood flow to part of the brain (cerebrovascular accidents), blood clots, and breast cancer.

- Hormone therapy does not need to be routinely discontinued in women aged older than 60 or 65 years.

- Managing the risk of MHT by using the lowest effective dose and non-oral routes of administration (if possible) becomes increasingly important as women age and with longer duration of therapy.

- Longer durations or extended use beyond age 65 should include periodic re-evaluation of risks and benefits, and consideration of periodic trials of lowering or discontinuing hormone therapy.

- For women with GSM, low-dose vaginal ET may be considered for use at any age and for extended duration, if needed.

- Unless there are strong medical reasons, a woman should determine her preferred hormone therapy formulation, dose, and duration of use based on continued assessment and shared decision-making with her healthcare professional.

Bioidentical Hormone Therapy

Bioidentical hormones are synthetic compounds that are manufactured to mimic natural hormones. They are intended to interact with hormone receptors in the body in the same way as natural, or conventional, hormones. [2] [4] [15]

There are safety concerns with the use of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy including minimal government regulation and monitoring, the risk of overdosing or underdosing, the presence of impurities, a lack of scientific data on effectiveness and safety, and poor or absent risk labeling. [2]

In addition to the risks associated with conventional, fully-regulated hormone therapies, there are additional risks with bioidentical hormones. These risks are due to the absence of regulatory oversight. Consider that government-approved (FDA-approved) bioidentical hormones, including estradiol and estrone, are regulated, are monitored for purity and effectiveness, come with extensive product information, and include warnings for any potential adverse effects. Any FDA-approved products also undergo extensive clinical testing and reporting.

Compounded bioidentical hormones are made at a compounding pharmacy using a prescription from a health-care provider. Compounding a product can be necessary if there are allergies or sensitivities to ingredients found in medicines made by a pharmaceutical company. Bioidentical hormones may combine multiple hormones such as estradiol, estrone, estriol, dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA], testosterone, and/or progesterone, and may use untested, unapproved combinations or formulations. As well, they can be offered in untested applications such as subdermal implants.

Bioidentical hormones are often prescribed based on the use of salivary testing, however this type of testing for MHT is considered to be unreliable. The issues are due to how hormones travel throughout the body (call pharmacokinetics) and differences in how they are absorbed, variations in hormone levels throughout the day and individual variations in hormone levels that are seen in saliva (compared to urine or serum levels for example).

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2022 updated hormone therapy position statement, which is endorsed by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC), reads:

- Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy presents safety concerns, including:

- minimal government regulation and monitoring,

- overdosing and underdosing,

- presence of impurities and lack of sterility,

- lack of scientific efficacy and safety data, and

- lack of a label outlining risks.

- Salivary and urine hormone testing to determine dosing are unreliable and not recommended. Serum hormone testing is rarely needed.

- Shared decision-making is important, but patient preference alone should not be used to justify the use of compounded bioidentical hormone preparations, particularly when government regulated bioidentical hormone preparations are available.

- Situations in which compounded bioidentical hormones could be considered include allergies to ingredients in a government approved formulation or dosages not available in government approved products.

The Science

The endocrine system is made up of a series of glands that produce and secrete hormones directly into your bloodstream for use throughout the body. The hormones are used for a wide range of functions (beyond reproduction in women) and act as chemical messengers throughout the body. The endocrine system works by sending signals from your brain to different glands that secrete specific hormones for specific purposes.

This table shows the most important hormones during the menopause transition, what the hormones are, where in the body they are produced and what they do in the body. [16] [17] [18]

NAMS 2022 Updated Hormone Therapy Position Statement

In July 2022, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) released an update to the 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement. NAMS used an Advisory Panel of experts in the fields of women’s health and menopause (both clinicians and researchers) to review the 2017 Position Statement, evaluate new literature, assess the evidence, and reach consensus on updated recommendations.

Highlights from this update include:

- Hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture.

- The benefits of hormone therapy outweigh the risks for most healthy symptomatic women who are aged younger than 60 years and within 10 years of menopause onset.

- The decision to use MHT should be a shared decision between a woman and her healthcare provider. The decision should be re-evaluated periodically over the course of treatment as a woman ages to ensure the use of appropriate doses, durations, and routes of administration required to manage a woman’s symptoms and to meet treatment goals.

- Risks should be assessed using both age and time since menopause.

- Transdermal (through the skin) routes of administration and lower doses of hormone therapy may decrease risk of blood clots and stroke.

- Women with primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) and premature or early menopause have higher risks of bone loss, heart disease, and cognitive or affective disorders associated with estrogen deficiency. It is recommended that hormone therapy can be used until at least the mean age of menopause unless there is a strong reason not to use MHT.

- There are not enough randomized, controlled trial data to be definitive about the risks of extended duration of hormone therapy in women aged older than 60 or 65 years. Observational studies suggest there is a potentially rare risk of breast cancer with increased duration of hormone therapy.

- For some survivors of breast and endometrial cancer that do not find any relief of their GMS menopausal transition symptoms from non-hormone therapy, observational data show that of low dose vaginal estrogen therapy appears safe and greatly improves quality of life for many.

- Breast cancer risk does not increase with short-term use of estrogen-progestogen therapy and may be decreased using estrogen alone (ET) therapy.

- There are safety concerns with the use of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy including minimal government regulation and monitoring, the risk of overdosing or underdosing, the presence of impurities, a lack of scientific data on effectiveness and safety, and poor or absent risk labelling.

- Hormone therapy does not need to be routinely discontinued in women aged older than 60 or 65 years and can be considered for continuation beyond age 65 for persistent VMS, quality-of-life issues, or prevention of osteoporosis after appropriate evaluation and counseling of benefits and risks.

- For women with GSM, vaginal estrogen or other non-estrogen therapies may be used at any age and for extended duration, if needed. [2]

Statistics

It is uncertain whether MHT will increase your personal risk of breast cancer since breast cancer risk varies based on the type of MHT plus a woman’s family history and overall health.

To date, the evidence shows that in North America, the estrogen in MHT does not cause, nor increase the risk for breast cancer overall.

In menopausal women, short-term MHT using estrogen will not increase a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer. However, MHT may slightly increase the risk for breast cancer in late menopause after 4 or more years of continuous use.

Some women are at high risk for breast cancer. Please discuss your personal risks when discussing MHT with your healthcare provider.

Risk Factors for Breast Cancer:

- Age (your risk increases significantly after age 55)

- Family history / genetics (e.g. BRCA 1 or 2; PALB 2 variants)

- Previous breast biopsy that showed abnormal cells

- Increased breast density on mammography

- Not bearing children (or having first child after age 30).

- Lifestyle

- Lack of exercise

- Excessive alcohol intake

- Obesity and weight gain after menopause

- Smoking

- Lack of breast-feeding after childbirth

Short-term use of MHT for symptom control and quality of life will have little effect on personal breast cancer risk. Longer use of MHT does increase breast cancer risk. Currently, the only proven strategy to reduce breast cancer deaths is early detection through mammography in women over 50.

MYTH

Osteoporosis is a biological process of bone density loss and increased bone breakage. It is part of the natural aging process for both men and women. Strong bones depend on many factors including your genetics, how you grew during puberty, exercise levels, your diet, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Your bones are at peak strength and density around age 30.

MHT including estrogen is very effective at supporting bone density and strength, especially when combined with a healthy lifestyle. As well, strength training such as weight lifting or even standing instead of sitting, plus a good diet including calcium and vitamin D3 can help maintain bone strength.

Mid-life sees many hormone changes. Those plus decreased physical activity can contribute to osteoporosis, which can affect you in your early 50’s, causing low-impact bone breaks.

MYTH

MHT can benefit women with mild-to-moderate common symptoms such as

- Vaginal weakness and dryness (vaginal atrophy)

- Urine leak

- Hot Flashes

- Osteopenia or weakened bones

Please talk to your healthcare provider about any of your health concerns. Many are manageable and some can be moderated with simple behavioral changes.

MYTH

Risk for colorectal cancer increases with age. Menopause transition and MHT/HRT themselves do not increase your risk for colorectal cancer. It is unclear right now whether MHT protects you against colorectal cancer. If you do not already, please start medical screening for CRC starting at age 50 as part of your overall self-care regimen.

MYTH

Data about the influence of MHT on stroke are mixed. MHT may increase the incidence of stroke, but this is nullified in women who exercise moderately. A stroke (ischemic stroke) is a clogged blood vessel blocking blood flow to the brain. Without blood flow and oxygen, brain tissue will die. Strokes can lead to serious losses of brain function. Strokes are the third leading cause of death in Canadian women and the risk for stroke increases with age.

The key to reducing the risk of stroke is a healthy lifestyle. The risk factors are:

- Hypertension

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Excessive alcohol

- Lack of exercise

- Diabetes

- Migraine headaches [with visual aura]

- Too little or too much sleep

Please discuss your personal risks for stroke when discussing MHT with your healthcare provider.

MYTH

MHT alone does not increase the risk of a heart attack. Heart attacks are the number two killer of women in Canada. Healthy perimenopausal women benefit from a protective effect from MHT and in fact have a lowered risk of heart attack.

Post- menopause, as a woman grows older, the risks of heart disease increase. Risks for MHT are age and life-style related.

The seven major risk factors for heart disease can all be modified, so a woman can adjust her lifestyle and reduce these risks. These risks are:

- Smoking

- Abnormal lipid profiles (seen from blood tests ordered by your doctor, these can include high blood levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol or fats called triglycerides)

- Hypertension

- Abdominal obesity

- Poor diet

- Excess alcohol

- Chronic stress

If you have any of these risk factors in your life, tell your healthcare provider when you are discussing hormone therapy.

MYTH

Hormone therapy for treatment of menopausal symptoms was thought to increase the risk of a woman’s chance of breast cancer, stroke and blood clots. This evidence has been re-evaluated, and MHT using estrogen has been shown to be safe and effective. [6] [8] What is now known is:

- MHT remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms and genitourinary syndromes of menopause and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture.

- The risks of MHT differ depending on the type of hormones, their dose, duration of use, route of administration, timing of initiation, and whether progestogen is used.

- Treatment should be individualized to identify the most appropriate MHT type, dose, formulation, route of administration, and duration of use.

- MHT must use the best available evidence to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks.

- MHT needs periodic reevaluation for the benefits and risks of continuing or discontinuing MHT.

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), also known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), is generally safe if you work together with a qualified healthcare provider. MHT is known to help many women with hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and keeping bones strong among other symptoms.

1. http://www.menopause.org

2. Melmed et al.Williams Textbook of Endocrinology 14 th edition.

3. Santoro_2016_Perimenopause: From Research to Practice

4. Allshouse et al._2018_Menstrual cycle hormone changes associated with reproductive aging and how they may relate to symptoms

5. Dasai and Brinton_2019 Autoimmune disease in women: endocrine transition and disease across lifespan

Hot flashes can be addressed in many ways but it’s best to collaborate with your care provider to find a therapy that works for you. Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) can be effective at reducing the frequency and intensity of hot flashes for many women. Antidepressants, meditation and relaxation techniques work also well as they lower stress hormones. Ensuring you are eating a well-balanced nutritious diet can also help.

Bio- identical hormones are reproductive steroid hormones, such as estrogen or progesterone, used in menopausal hormone therapy (MHT). The term “bio-identical” means the hormones in the MHT product are chemically identical to those your body produces.

Bio-identical hormones can be easily recognized and used by our bodies so the effects are more consistent with our natural biochemistry. As well there is a smaller risk of unpredictable side effects than with synthetic or non-bio-identical hormones.

There are FDA approved bio-identical hormones that are safe and effective, but there is no evidence to date that bio-identical hormones are more effective or safer than synthetic hormones. There are also FDA approved natural hormones that are derived from plants.

There are options to help reduce or manage some symptoms. The primary tool is called menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), also called hormone replacement therapy (HRT), menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or hormone management therapy (HMT). MHT is helpful for decreasing hot flashes, improving the health of your vagina and urinary systems, and supporting your muscle and bone health and strength.

Unfortunately, other symptoms may not respond as well to MHT. Physiotherapy can help with physical pain and psychological counseling and therapy can help with emotional troubles. Lifestyle changes to promote quality sleep, good nutrition, and exercise are important and known to decrease menopausal transition symptoms.

Why enquire about hormone therapy?

Decrease

The frequency and intensity of hot flashes and night sweats.

Preserve

Bone mineral density and fracture incidence and risk.

Reduce

Vaginal dryness.

Improve

Quality of sleep.

Decrease

Body aches that are not related to bone loss.

Improve

Urinary Control.

Compiled References

[1] Antunes CM, Strolley PD, Rosenshein NB, Davies JL, Tonascia JA, Brown C, Burnett L, Rutledge A, Pokempner M, Garcia R. Endometrial cancer and estrogen use. Report of a large case-control study. N Engl J Med. 1979 Jan 4;300(1):9-13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197901043000103. PMID: 213722.

[2] The NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause: The Journal of The North American Menopause Society Vol. 29, No. 7, pp. 767-794 DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

[3] Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: Principal Results From the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321

[4] R. J. Baber, N. Pa nay & A. Fenton the IMS Writing Group (2016): 2016 IMS Recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy, Climacteric, DOI: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1129166

[5] Bulun. Physiology and pathology of the female reproductive axis. William’s Textbook of Endocrinology, 14th edition. Elsevier, 2019.

[6] Minkin MJ. Menopause: Hormones, Lifestyle, and Optimizing Aging. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019 Sep;46(3):501-514. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2019.04.008. Epub 2019 Jun 21. PMID: 31378291.

[7] Umland EM, Falconieri L. Treatment options for vasomotor symptoms in menopause: focus on desvenlafaxine. Int J Womens Health. 2012;4:305-319. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S24614

[8] The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society.

[9] Attarian H, Hachul H, Guttuso T, Phillips B. Treatment of chronic insomnia disorder in menopause: evaluation of literature. Menopause 2015;22:674-684. PMID: 25349958.

[10] https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-menopausal-symptoms-with-hormone-therapy

[11] Utian, W. H., & Woods, N. F. (2013). Impact of hormone therapy on quality of life after menopause. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 20(10), 1098–1105. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318298debe

[12] Pines, A., Sturdee, D. W., & MacLennan, A. H. (2012). Quality of life and the role of menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric : the journal of the International Menopause Society, 15(3), 213–216. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.655923

[13] Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, et al, WHIMS Investigators. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2651-2662. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651

[14] Craig, M. C., Maki, P. M., & Murphy, D. G. (2005). The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: findings and implications for treatment. The Lancet. Neurology, 4(3), 190–194. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01016-1

[15] Harvard Health Publications, Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu/press_releases/myths-and-truths-about-bioidentical-hormones

[16] You and Your Hormones (The Society for Endocrinology) https://www.yourhormones.info/hormones/follicle-stimulating-hormone/

[17] https://www.endocrineweb.com/endocrinology/introduction-endocrinology-endocrine-surgery

[18] Melmed, S., Polonsky, K. S., Larsen, P. R. & Kronenberg, H. M. (2016) Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier.

[19] SOGC 2018. Hormone Therapy Products available in Canada for the Treatment of Menopausal Symptoms, Physician Desk Reference – 3rd edition

[20] https://www.cemcor.ubc.ca/resources/topics/sleep-disturbances

[21] Modi M, Dhillo WS. Neurokinin 3 Receptor Antagonism: A Novel Treatment for Menopausal Hot Flushes. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;109(3):242-248. doi: 10.1159/000495889. Epub 2018 Nov 30. PMID: 30504731.

Page last updated May 16, 2023.

Bleeding Issues

Bleeding Issues Skin, Hair & Nails

Skin, Hair & Nails Mood Changes & Rage

Mood Changes & Rage Depression

Depression Cognitive Changes

Cognitive Changes